“It is the only photograph of Lotte and Carl Hirsch, my parents, taken during the war years, and it is tiny, 2.5 × 3.5 centimeters, about the size of a 35-millimeter negative, with unevenly cut edges. I have always loved this image of a stylish young couple – newlyweds walking confidently down an active urban street. The more difficult it was to make out the details of the faded and slightly spotted black-and-white image, the more mysterious and enticing it became to me over the years.” (1) – with this description of an extremely personal photo Marianne Hirsch (American Holocaust researcher, author of the “postmemory” term, holocaust survivors’ daughter) begins one of the chapters in her book “The generation of postmemory”.

A photo of the Jewish couple, taken in 1942 in Czernowitz – a part of fascist Romania at that time, – attracts attention, in the first place, by being openly plain: it’s the most usual photo of two people in love, taken by a random street photographer. It looks strikingly different from what we would think a photo of Jews taken during the World War II should look like.

This inconsistency between what is commonly known from history and what she sees on the photo from her own familial photo archive prompts Hirsch to perform a certain investigation: she starts to scan the photo for the smallest hints of the times and the tragic fate that had spared her parents but had passed very close nevertheless. The photo is digitised and enlarged, and a grey spot on Marianna’s father’s jacket comes into view, the spot that might look similar to a six-pointed star. Hirsch sends the photo to her parents.

“‘There is a small spot on my lapel,’ Carl wrote in an e-mail, ‘but it could not be the star. The stars were large, 6 centimeters in diameter. Maybe I should have written 1943 on the photo. They did away with the stars in July of 1943.’ ‘And if that is a star,’ Lotte wrote, ‘then why am I not wearing one?’” (2) Other photos of Jews with stars from Czernowitz are really dated 1943. Interviewing her parents did not bring answers, it only asked new questions instead.

This example helps us understand how uncertain the images of the past created by the spectator based on the archival photos can be; how fragile is the world, that the spectator is trying not even to see but rather to reconstruct themselves beyond the picture’s frame; and how little, in fact, can even the visible details tell. The desire to find a six-pointed star in the old photo turns out to be stronger than the eye’s physical capability to discern it; the date on the back can deceive; and the participants of the event can no longer tell anything about it, having lost it in a series of more important days and events.

In other words, archival photos as material artefacts of memory neither supply information nor shed light on the nature of the event that they depict, as much as they reflect the feelings of the spectator who interacts with them; demonstrate his perception of what cannot be seen in these photos and what remains beyond the frame but is known to them from other sources. The “picture’s indexicality is more performative – based on viewer’s needs and desires – than factual,” concludes Hirsch (3).

This example is quite radical but – regardless of whether archival photographs are witnesses of the traumatic event or not – our perception of the image is shaped by what we know about the past and about the subsequent fate of the people in the photo; by our emotions, experiences, and imagination.

Nevertheless, even though the role of photography as historical document is limited, it can function as “points of memory“, which serve as a supplement to historical facts and eyewitnesses’ reports, helping to establish the emotional and material connection with the past, where the photo itself is both the symbol and the instrument of such connection.

In this aspect, the important element of establishing this connection is the possession of the photography as an object, its physical presence in the personal archive, the materiality with which the beholder interacts: the ability to grab the photo, turn it around, look at it closer, or at different angles. In her book “Photographs as objects of memory” Elizabeth Edwards writes: “The materiality of the photograph is integral to its affective tone as an image. The subjective and sensuous experiences of photographs as linking objects within memory are equally integral to the cultural expectancies of the medium, the certainty of the vision it evokes and cultural notions of appropriate photographic styles and object-forms for the expected performance of photography in a given context.” (4)

Here, the materiality of the photography as an image is none the less important than the depicted image itself – the size of the print, its state, printing method, marks on the back, the photography’s place in the album – all of these influence our imagination, helping to analyse it or, on the contrary, rendering the analysis practically impossible, adding new meanings or erasing the old ones.

After losing, for any of the reasons, access to family photos, one remains empty-handed: their ability to restore the connection with their past is now based solely on the work of their own memory and imagination, where the memories of the events are supplemented by the memories about the photographs, which now instead of being memory’s substitutes and its material confirmation became memories themselves.

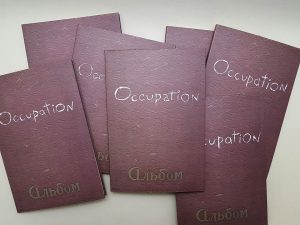

And it is exactly this function of the postmemory mechanisms and memorising in the context of the family archive that lies in the core of Andrii Dostliev’s “Occupation” project. In “Occupation”, the process of restoring the events of the past is, in a way, reversed: it’s the photos that are being reconstructed now based on the memories.

The photos which the author has no access to anymore – his familial photo archive remains in occupied Donetsk, as he writes in the project’s description.

“Occupation” is a series of collages, carelessly constructed of anonymous photos from flea markets and touristic postcards. Each reconstructed picture is accompanied by the detailed description.

The series starts with a female black-and-white portrait in three-quarter view: a young woman in white blouse and black jacket looks past the photographer, slightly smiling, the blouse collar is pinned with a large brooch.

“This woman in the photo from the flea market in Riga looks remarkably like my grandmother in her 30s. She had a similar photo – same pose, same three-quarter view, similar clothes. She must have liked it – she even had an enlarged hand-coloured copy made. The aubergine sleeveless dress she’s wearing in this photo lasted long enough for me to remember it.”

The text here bears more importance while the image is purely illustrative, indexical: it doesn’t matter that the woman is wearing different clothes and that the effect of a “hand-coloured photo” is achieved using acrylic paint. The phrase “This woman … looks remarkably like my grandmother” actually means not that the woman on the photo really looks like the author’s grandma but rather that he recognises his grandma in her.

In her book “Touching Photographs” Margaret Olin based on Roland Barthes’ “Camera Lucida” introduces the notion of a “performative index” or an “index of identification”: “a reading of Camera Lucida suggests that the most significant indexical power of the photograph may consequently lie not in the relationships between the photograph and its subject but in the relationships between the photograph and its beholder, or user, in what I would like to call “performative index” or an “index of identification” (5).

The “index of identification” plays a very important role in “Occupation” – the reconstruction of the photos is based on the details which initiate the mechanism of recognising, meanwhile everything else, which has no importance for the identification, is either cut off, painted over, or simply ignored. This newly reconstructed archive made of other people’s memories is visually held together only by the author’s desire to illustrate his personal history.

The second photo in the series is a group photo, also black-and-white: two elegantly dressed young women seated next to two standing men in Soviet military uniforms. The pictures of the soldiers are carelessly cut off and attached along with pieces of background, their proportions are distorted, the soldier on the right is missing an arm.

“This picture was particularly important to my grandmother. It was taken shortly after the nazi forced labor camp in Sudetenland where she was held was liberated by the Soviet army. She and her friend and two soviet soldiers made a group portrait in the studio to celebrate the first moments of their freedom.”

In this case, the photo is restored from the anonymous pictures based not only on the memory of the initial image but also on the eyewitness’s report; archival photographs are being appropriated to reconstruct personal memories. A similar approach can be seen, for example, in Art Spiegelman’s “Mouse” – in its first 1972 version there is a redrawn photo by Margaret Bourke-White, which initially showed the liberation of Buchenwald (Survivors gaze at photographer Margaret Bourke-White and at their rescuers from the United States Third Army during the liberation of Buchenwald, April 1945). On the edges there are corners like there used to be on the photos in the albums – a public image is appropriated and is assigned a place in the personal album, it now becomes a part of a personal history. Thus, the individual memory is reconstructed using social and cultural memory mixed with postmemory.

The next image attracting attention is a group black-and-white photo, the dress of the woman in the centre of the composition was cut off and replaced with a piece of bright pink and white checkered paper, the eyes of everyone in the photo were painted white.

“This picture used to give me creeps when I was a child. Grandma and her colleagues from school are all dressed in black except for one woman in the first row – she’s wearing something bright and chequered. The photo had faded over the years and eyes had become blank spaces without any sign of pupils.”

The original picture clearly hints at a different, more solemn event – it was, most likely, a wedding photo made in a studio, and the woman in the front row, whose dress was cut off and made “something bright and chequered”, was the bride, but these details are secondary and unimportant for the author, while the beholder would first stumble upon the colourful pattern and after that be absorbed by the empty white eyes of the people who look like they came out of a horror movie or a nightmare.

There is no talk here of the authentic reconstruction of the events or the subject of the original photo – what is reconstructed are the feelings of the contact with the image, the experience of a child, who looks at the faded picture, at first staring at the patterns on the dress and trying to guess its colour, then confronting the gaze of the empty white eyes and not daring to look back at them, tries to concentrate on the dress, imagining it brighter and brighter, bright enough to attract all the attention from the steady blank gaze.

Returning to Roland Barthes, it can be said here that the images of this kind, which are quite numerous in the series (the old lady with the golden tooth, uncle’s wedding, semi-naked child in the grass, portrait with the monkey, etc.) are based on reconstructing the details which represent punctum for the author and the carelessness of the technique they are made in highlights the lack of importance, the “unnecessity” of the details not connected with the punctum.

The next image displays a stocky old woman wearing a shawl in the countryside. There are not many details of her surroundings left because the left part of the photo is roughly torn off. The author explains: “My grandfather’s sister… Half of the photo was torn off and I never got to know who was in it. Maybe it was her husband whom she had killed with an axe – in self-defence.”

What is particularly interesting here is the attempt to reconstruct the “non-existence”, emptiness, gap, which the author himself had filled in his childhood with a history of violence, something more suitable in the criminal chronicles than in the personal family mythology.

Ulrich Baer pointed out that such photographs in the context of trauma create something that can be called “spectral evidence”, something that reveals “the striking gap between what we can see and what we can know” (6).

The beholder starts to reconstruct what is left behind the frame, what this woman had to face before she resorted to such a radical self-defence method, who was her husband and what did he look like. And even though we would most likely take her side here, we cannot be completely sure whom do we see in this picture – a victim or a criminal, what was really torn off with the left part of the picture, and how true is the story we’ve been told.

The series ends with a colour group photo, where faces of some of the people are crossed with black X marks.

“One of the last analogue family photos made in Donetsk. Plenty of people, some of them I hardly know, some do not belong to our family anymore, a few are dead, others chose now to collaborate with terrorists and rather were dead.”

This picture takes us back to the beginning of the story, to the traumatic event that lies at the core of the project: some of my relatives became collaborators, they support Russian occupants, who have forced me and two million more people out of our homes and our pre-war lives; I wish they were rather dead.

Paul Connerton, a professor of Social Anthropology, in his classification of the types of forgetting distinguishes the so-called repressive erasure (7) – a forcefully introduced mechanism of forgetting, characteristical to totalitarian regimes, when the memory about people considered undesirable by the regime (and often repressed by the same regime) is removed from the public space. Monuments are being demolished, street names changed, photographs removed from the archives, destroyed, or edited and from this time on reproduced without these people. In “Occupation”, repressive erasure is applied to relatives-collaborators as a substitute of physical harm; being unable to cause adequate damage in return, revenge for the destroyed peaceful life and for the home city, occupied and turned into a shady criminal zone, the author symbolically erases these people from his memory. They were crossed out of the newly written family history, all that remains is an empty space they could have filled in a reconstructed myth about the past.

When talking about the reconstruction of family album as a particular case of the reconstruction of material memory, I think it is important to consider whether such reconstruction is possible at all. And I don’t mean reconstructing physical objects or producing significant works of art (an example of which was our – Andrii’s and mine – joint curatorial project “Reconstruction of Memory”), but rather the very possibility of creating an object capable of satisfying the same needs as the one that is being reconstructed.

The photo from the family album is important for us only as long as we are capable of discerning the faces of people in this photo and relating them to the faces of people close and important to us, those whom we remember from our childhood or know from elder relatives’ stories. The emotional link with the referent is what makes a certain archival picture important to us, what makes it stand out from all the other similar pictures. For a stranger not belonging to the family, our relatives’ photos would only be some of the many featureless archival photos that might uncover totally different senses; their gaze could stop at the clothing features, surrounding objects, signs of time, – or just pass by.

Here I’d like to refer as an example to the story opening Marianne Hirsch’s book “Family Frames”:

“When my book The Mother/Daughter plot was published I decided to send a copy to my cousin Brigitte who lives in Vienna. (…) She called almost immediately, exclaiming over the picture that was on the cover on the book, a picture of my grandmother and aunt – her great-aunt and cousin: ‘So that’s who that woman is! I have boxes full of pictures of her, and when I last went through them we all had to laugh about her strange hats and get-ups.’ I was both thrilled about the prospect of having access to family pictures I had not known about, and somewhat taken aback that my grandmother, decades after posing for her pictures in what must have been her most elegant outfits, should have been laught at so unthinkingly and irreverently. (…) I asked if I could go through her collection on my next visit to Austria, or if she would send me the ones of the woman with the strange hats. I was eager to save my grandmother from further ridicule, however benign, to reinscribe her into the albums where she would be known, recognized, respected. But, when my cousin looked for the old photos, she could no longer find them. Her husband had cleaned house and they were gone.” (8)

Is it possible in this context to replace your own photos with somebody else’s, which would in some way respond to your need to see the familiar and beloved features? When we were starting to work on our “Reconstruction of Memory” project, I had a chance to research for myself the possibility of reconstructing my own archival photographs from our familial album, which also remains in the occupied territory. I took the path of formal resemblance and tried to reconstruct one of my favourite family pictures using pieces of anonymous archival photos: Donetsk, 1961, my grandma and grandpa stand at Lenin square in front of the Ministry of Coal Mining Industries, grandma is holding my father, he’s about one year old. I was eager to make this new photo as much alike the original as it was possible. I meticulously recreated the composition, the proportions, the postures, I managed to find among other people’s photos the ones of the same age and wearing similar clothes, I even got a picture of a man wearing the same type of hat as my grandpa wore when he was young. The resulting photo was so close to my memory about the original that I started to feel uneasy.

I put this picture on the wall and then asked our 9 y.o. son, what he thought of it. Instead, he asked me back if it was one of those photos he had seen at our home in Donetsk (we often used to browse old albums) with elements of my artistic intervention. Despite fulfilling the formal criteria of similarity and even despite my child’s eagerness to recognise this photo (or eagerness to respond to my desire for this photo to be recognised), I still kept perceiving the image as something deeply wrong. Each time I looked at the wall where this reconstructed photo hung, I experienced unexplained anxiety.

Returning the lost would, on one hand, mean the possibility of losing it again, the repetition of a pain that already started to subside. On the other hand, the reconstructed photo took me back to the time when either people in this photo were alive or the cosy little homely world was intact, the world where the memory about these people used to function as an integral part of everyday life and the albums were peacefully standing on their respective shelf in the bookcase and always were within reach.

Thus, the reemergence, the return from the void of such a picture, which would arouse the same emotions as the original, seemed in a way to nullify everything that had caused her disappearance, everything that cut the link with the past and interrupted the continuity of the personal history. The return of my archive seemed to question the reality of everything that had happened to me and my country in the course of these three years: the war, the numerous deaths, the panic relocations, destroyed buildings and human relationships. The existence of this construct felt like something intolerable, threatening, morally unacceptable, something that has no place in my present.

“Occupation”, as opposed to my visual research, does not pretend to reconstruct the objects of material memory which would satisfy the same needs as the lost ones. The irony and the carelessness of the technic create a certain distance between the author and the traumatic event: the series claims to be the intentionally imperfect reconstruction which cannot be as good as what was lost (and does not aim to) but mimics it in a grotesque, distorted, and sarcastic way, having no pity for its own vision of the past, the evidence of which it attempts to restore.

The photographs were chosen by the author according to one principle – these pictures are personally valuable for the author and record his loss, the rupture in the continuity of his personal history. But the story of one family is told in such a way that there remain literally no unique facts or events which cannot be equally incorporated into anybody else’s history. The scenes in the restored album are typical and recognisable. Similar ones can be found in any generic family album: naked children in the countryside, studio portraits, photos from the holidays, more or less successful amateur snapshots with everyday life scenes, mixed with references to historical memory. Private is generalised to the maximum here and is reconstructed in such form, that it can belong to anybody.

In this context, “Occupation” becomes an illustration of the collective experience of the loss, while this reconstructed album – with minor derivations or generalisations – is also the album of any of the two million internally displaced Ukrainians.

1. Hirsch Marianne, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), p. 66.

2. Ibid., p. 70.

3. Ibid., p. 70.

4. Edwards Elizabeth, Photographs as Objects of Memory, in The Object Reader, eds. Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins (New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 332.

5. Olin Margaret, Touching Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 69.

6. Baer Ulrich, Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), p. 2.

7. Connerton Paul, Seven types of forgetting, in Memory studies, 2008, #1 (1), p. 60.

8. Hirsch Marianne, Family Frames (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. xi.